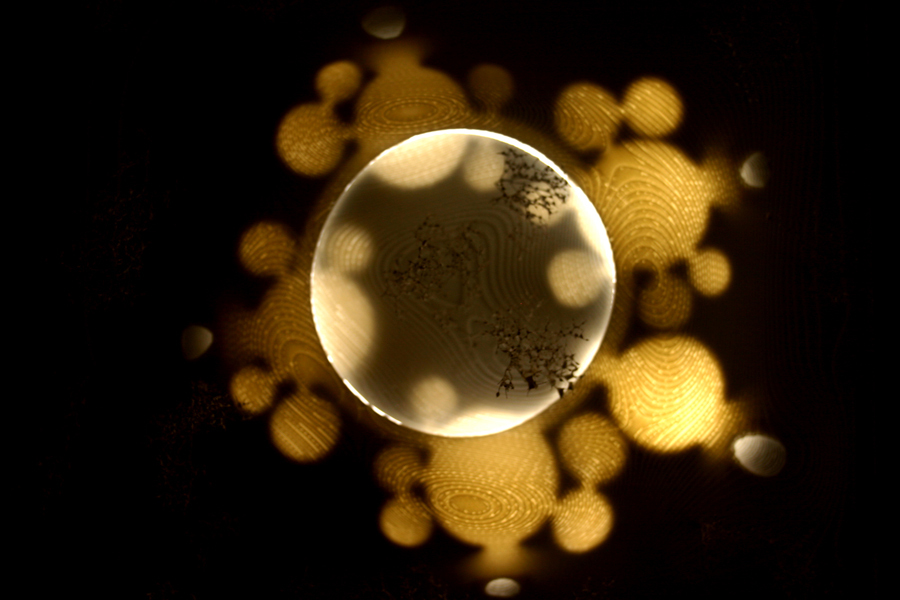

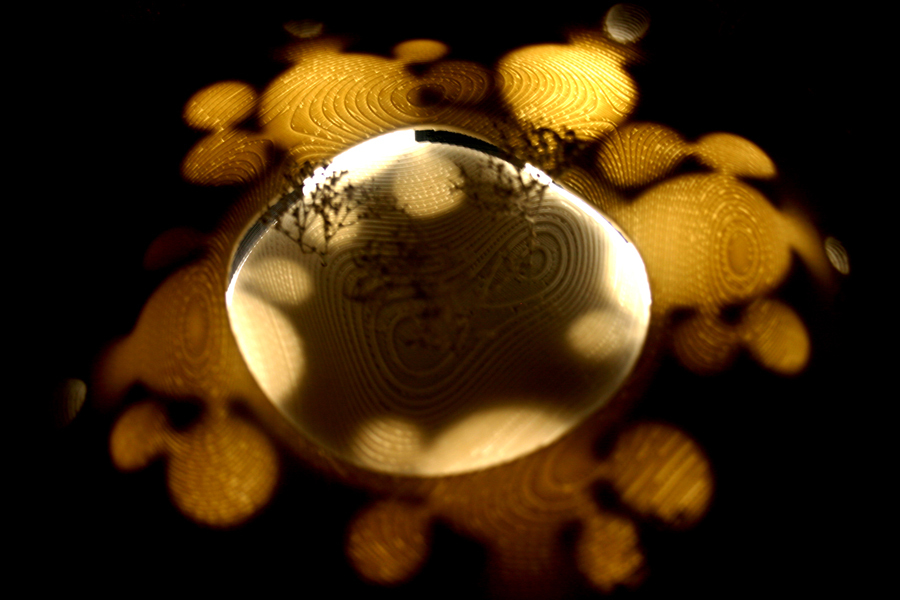

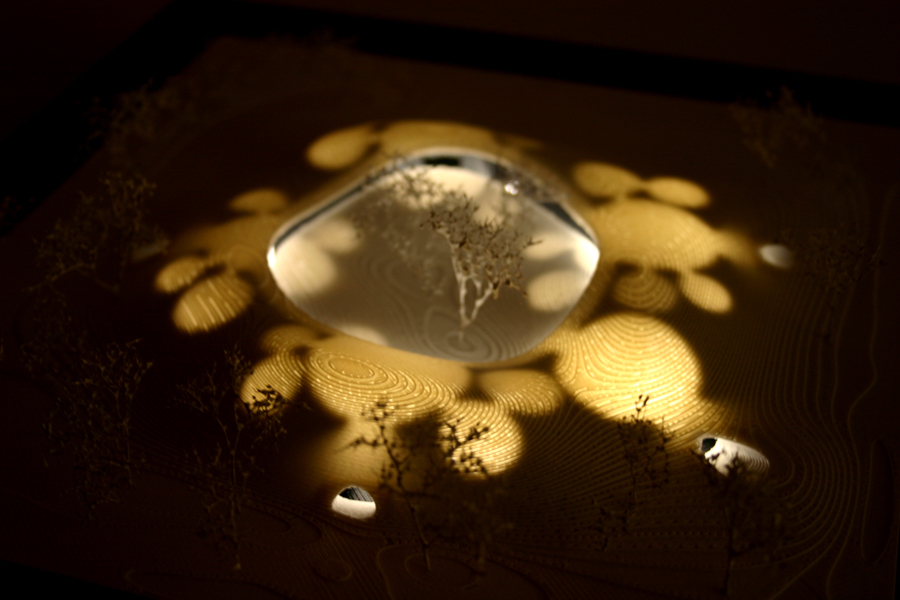

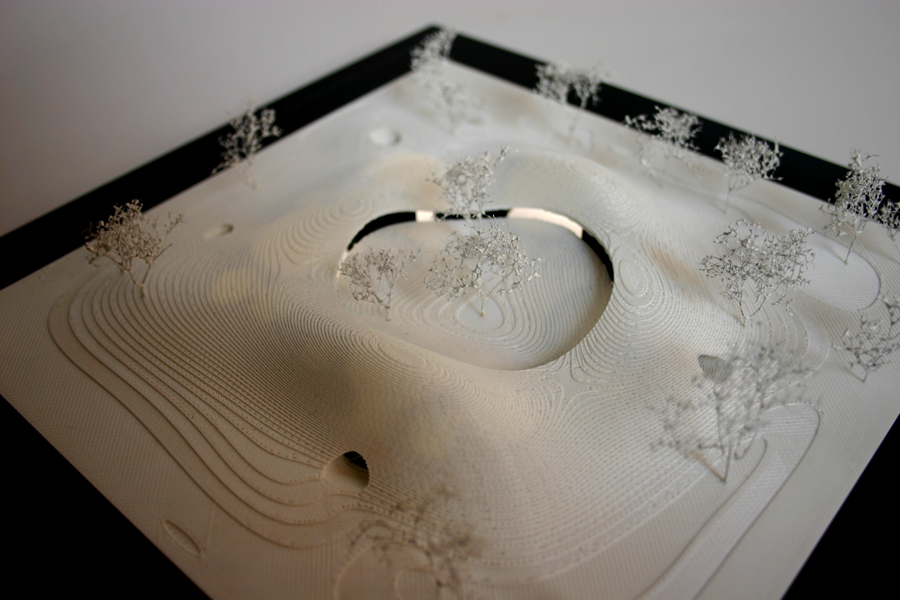

Model: Modelab, Photographer: Florindo Ricciuti

The planning of the ecumenical centre in the town of Arles, gives me the chance to look into the theme of the symbolism in architecture and to interpret again the link between icon and religion.

In all ages, during the planning of a place of worship, people tried to create mystic spaces that were able to establish a relationship with the Divinity, but that had to be a symbol, and at the same time, a landmark in the urban context.

The planning research turned into a linguistic research with the aim of introducing styles which could represent, at their best, the greatness of the Divinity; but, in the contemporary age, with the contamination of ethnic groups and religions and the co-existence in the same town of places of worship of different religions, the linguistic research turned into a process of self- identification, where, each cult tried to determine itself to become recognizable inside the metropolis.

The planning of an ecumenical centre, a place of meeting and exchange between different religions, where the co-existence of diversity of individual’s stories interweave, challenges all what has been said up to now.

It is inconceivable to plan a centre designed like a house, a mosque, a synagogue or a Catholic or Protestant church where one language is more dominant than the other. It would be like admitting the possibility of coexisting and putting up with the idea to live separated, as slaves of our own identity.

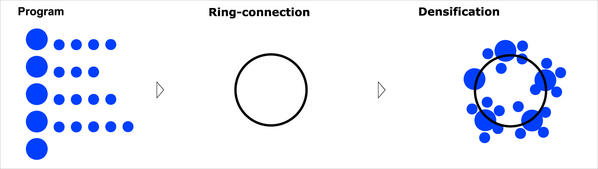

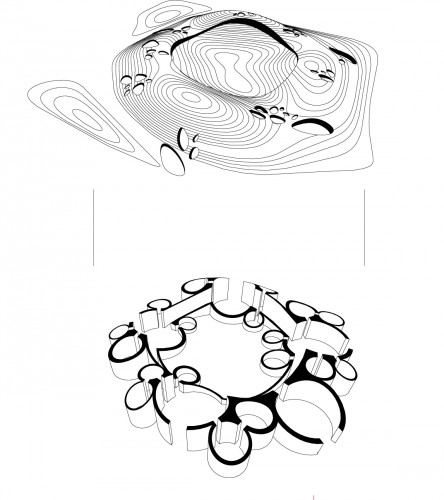

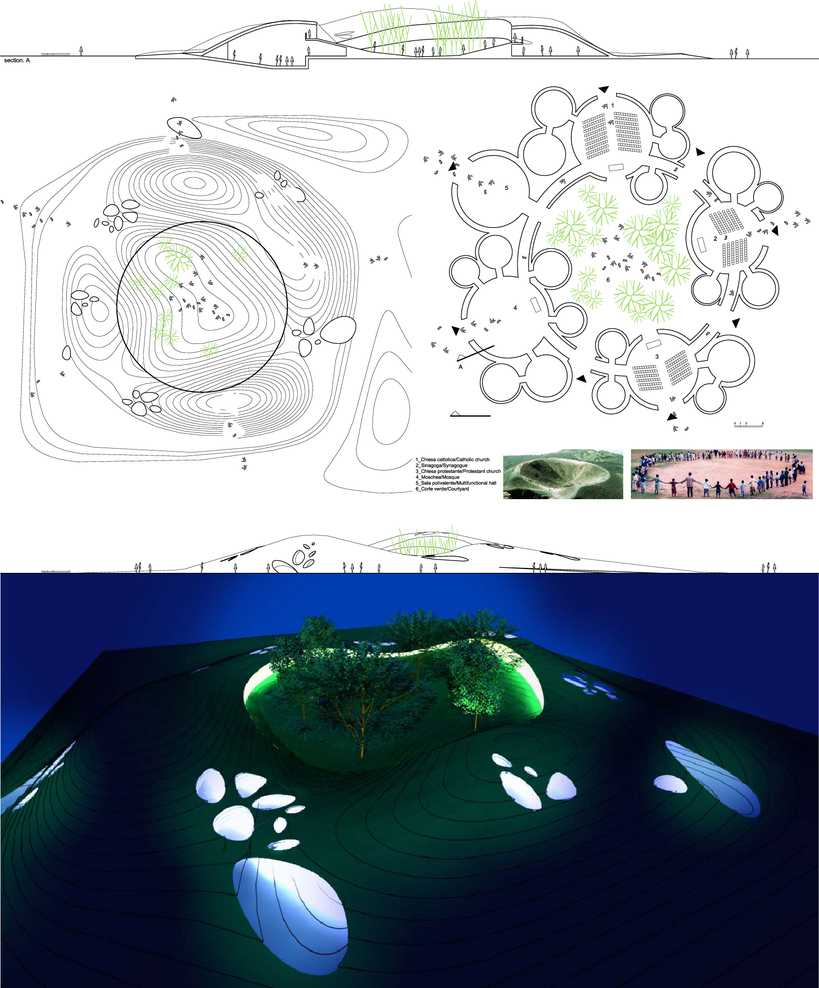

The suggestion of this ecumenical centre completely denies all symbolism, by placing all the buildings around a connective round-shaped path: a ring, which ideally links every religion and one which denies diversity. In order to state the idea of denial of every form of individualism, the entire structure is covered with earth, by creating some hills, wrapped with a green mantle.

The latter is engraved with amorphous holes to bring light inside, with large cuts which guarantee access to the buildings via caves, and above all, through a big circle cut through: a glass ribbon which wraps the inner courtyard, a place of exchange and meeting between cultures, the mystic space and the hidden secret beyond the hills.

Every single building is made of a central round–shaped nucleus, designed for religious ceremonies. Around this, the other environments orbit like satellites; as previously described, the five structures surround the big central courtyard, generating a continuous alveolar system.

The denial of the symbolism and the willingness to overcome the planning research generate a sculptural landscape: the Holy Hills. A sculpture designed to become the icon of the contemporary metropolis, a symbol of the racial integration, a symbol of the exchange and comparison between different ethnic groups! The Holy Hills deny symbolism to the individual to become a symbol of the entire community!

__

La progettazione del centro ecumenico della città di Arles mi offre l’oppurtunità di indagare il tema del simbolismo in architettura e di reinterpretare il rapporto tra icona e religione.

In ogni epoca nel progettare un edificio di culto si è tentato di realizzare spazi mistici in grado di instaurare un rapporto con la divinità, che al tempo stesso fossero un simbolo, ed un punto di riferimento nel tessuto urbano.

La ricerca progettuale si è trasformata in una ricerca linguistica, con lo scopo di introdurre stili che potessero rappresentare al meglio la grandezza delle divinità; ma nell’era contemporanea, con la contaminazione delle etnie e delle religioni, e la compresenza in una stessa città di luoghi di culto di differenti religioni, la ricerca linguistica si è trasformata in un processo di auto-identificazione, in cui ogni culto ha cercato di autodeterminarsi per diventare riconoscibile all’interno delle metropoli.

La progettazione di un centro ecumenico, luogo di incontro e di scambio tra le varie religioni, in cui coesistono diversità e si intrecciano storie di popoli completamente diverse, mette in crisi quanto finora discusso. E’ impensabile progettare un centro destinato ad accogliere una moschea, una sinagoga, una chiesa cattolica ed una protestante con un linguaggio predominante rispetto all’altro, sarebbe come ammettere l’impossibilità di convivere e rassegnarsi all’idea di vivere divisi, schiavi della propria identità.

La proposta di questo centro ecumenico nega completamente ogni simbolismo, disponendo tutti gli edifici intorno ad un percorso connettivo di forma circolare: un anello che idealmente unisce tutte le religioni negando ogni diversità. Al fine di affermare il concetto della negazione di ogni individualismo l’intero impianto è ricoperto da terra, dando vita a delle colline avvolte da un manto verde. Quest’ultimo è inciso con delle bucature amorfe, per portar luce all’interno, con dei grandi tagli, che come delle grotte garantiscono l’accessibilità agli edifici, e soprattutto da un grande cerchio incassato: un nastro di vetro che avvolge la corte interna, luogo dello scambio e l’incontro tra le culture, lo spazio mistico e segreto nascosto al di là delle colline.

Ogni singolo edificio di culto è costituito da un nucleo centrale di forma circolare, destinato alle cerimonie religiose, ed intorno ad esso gravitano come dei satelliti gli altri ambienti; come sopra descritto i cinque impianti circondano la grande corte centrale generando un sistema alveolare continuo.

La negazione del simbolismo e la volontà di superare la ricerca progettuale generano un paesaggio scultoreo: The holy hills. Una scultura che è destinata a diventare icona della metropoli contemporanea, simbolo dell’integrazione razziale, dello scambio e del confronto tra diverse etnie! The holy hills rifiuta un simbolismo individuale per trasformarsi in un simbolo dell’intera collettività!